|

terre thaemlitz writings 執筆 |

|

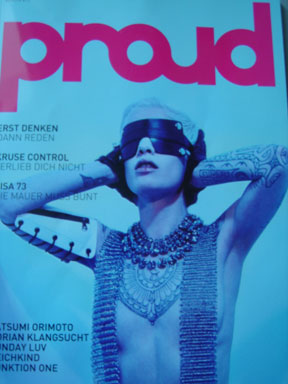

All's In Order "Out of Order" Fashion's Inability to Divest of Power - Terre Thaemlitz |

| Summary |

As if on cue, upon arriving in Germany to deliver this lecture I found the January 2010 edition of Proud magazine perfectly illustrating the commodified and populist death wish at issue. Featured designers include H&M, Tribecca, American Apparel, Nicone, Lisa D and others. |

|

Toy gun to the head.

Toy gun to the head.

|

Drug overdose. |

Toy IV drug overdose. |

Alchohol or poison. |

Pills and alchohol. |

Shooting oneself. |

Hanging oneself. |

As a fashion victim of another kind, who has no interest in commercial embrace or reconciliation, I have found "out of order" fashion's "anti-social yet commercially viable" concept of clothing to be even more oppressive and devious than evangelical prudery. The critique of dominant culture offered by impracticality and unwearability are no more than theatrics within an arena of mass spectacle, often reflecting a luxury of experimentation only granted by wealth and canonization. Unsellable fashion - the risqué face of a conservative industry - is more often than not the masturbatory privilege of corporate leaders whose lifestyle gluttony is funded by the bulk sale of their branded hand towels and sweat shirts to the less fortunate. It is the insulting cake offered up by Marie Antoinette. A cake we are all too eager to eat, as if without adverse implications.

Speaking of Marie, how many designers do you think would have refused participation in fashion films such as "Marie Antoinette" or "Elizabeth" on political grounds, refusing to associate with projects exalting feudalism at worst, or feigning ambivalence on the subject at best? I doubt you could find a single one. In this way, the suicide, or rupture, proposed by avant-garde fashion is rooted in a romantic identification with the prideful, arrogant death wishes of monarchs on the verge of dethronement; and not in the more realistic suicide of faceless, impoverished nobodies pushed to the brink by dominant social mores, principles and trends. This is because fashion, as an industry, remains enamored of patrons and the patron system. The fashion industry's complicity with the brutalizing moralities implied in the systems of domination it mutually supports and is supported by, all the while claiming to speak from a position of social-minded "principle," is the disgrace of "out of order" fashion. It is the arrogance that would, for example, lead people in fashion to cite the social acceptance of women's slacks as a case of the clothing industry transforming gender relations; a view which erases the material struggles of women who wore men's clothes in their attempts to gain male privileges such as suffrage, the right to own property, or even to join the military. Women who were sometimes beaten, raped and murdered as a result of their wardrobes. (Again, we come back to the lack of entertainment value placed on FTM and cross-dressing lesbians at parties, precisely because they remind us our capacity for humor is at times outweighed by the traumas of life without a penis under patriarchy.) Industry and distribution do not remind us of these bold and brutalized women, but actually erase our memories of their actions by saying the acceptance of women in pants was simply a matter of exposing enough people to a certain cut of cloth over a long enough period of time. The fact that male dresses remain a cultural oddity after nearly a century of women's slacks shows how little fashion is doing to dismantle the images of patriarchy, or to divest men of their traditions. To the contrary, women's slacks - as a symbol of women's liberation with no corollary male transformation - simply reaffirm associations between power and traditional male fashion under patriarchy.

As someone who is not interested in empowerment, but interested in divestments of power, the cultural changes proposed by the fashion industry - no matter how outrageous they my look on the runway - mean nothing to a person such as myself. Instead, I feel molested. Raped. Violated. In my lifetime I have seen the effects and signs of poverty - of wear and tear, and second-hand fashion - become co-opted by the rich. I have come to see torn T-shirts and tattered jeans sold for more than the cost of a month's rent. (That's one month of my rent - how many months rent for the third-world employees working in garment factories?) I see young Japanese punkers (who don't listen to punk rock at all, but listen to J-pop) wearing €500 pants, and €800 hair weaves, with not a single self-made or self-altered item on their bodies. I have seen people proudly walking around in Richmond jeans with the word "RICH" emblazoned across their asses - to which I responded by patching the word "BROKE" across the back of a pair of my own used jeans. And I have seen people around the world and of all classes swallow these trends, both in the form of the poor's fantasy-driven eagerness to see themselves in the rich, and as a means for the rich to camouflage themselves amidst those they exploit with ever increasing economic imbalances. I have seen every single signifier of my own experience twisted into blades wielded by the very industries and cultural systems I sought to resist. I stand empty handed. Which is precisely where I began back in Reagan-era Springfield, Missouri: surrounded by peers robbed of class consciousness; wealth and industry ridiculing poverty; the possibilities of guerilla fashion and fashion terrorism commodified and regurgitated back upon us as a privilege of excess, at which point we gobble it up off the floor like dogs. I'm getting too old for this shit... and this time around I can't afford the new clothes or the used ones, which is why I still wear clothes found in my father's basement.

What has changed are my reactions to these circumstances - changes largely mandated by the economics of adulthood (ie., the necessity for employment). Although we like to portray our student years in high school and university as the time for struggling with our relationships to identity systems, it was only after graduation that my real struggles with issues of gender and sexual representation began. The impossibility for gender-fuck within standard work environments (let alone everyday actions such as grocery shopping), combined with intolerance in personal relationships, resulted in a strict gender divide within my wardrobe. Daily life took place in male clothes. Similarly, my cross-dressing became traditionally feminine and concerned with "passability." Both wardrobes revolved around concerns for personal safety, ranging from the ability to maintain employment to avoiding being singled out for bashing on the street. And although in recent years I have minimized my use of cosmetics and wigs when dressed in women's clothes, this rather clear gender divide continues to dominate my appearance.

While the closets underlying this divide - both sociological and industrial - are not at all surprising, there were also unexpected closets over the years. For example, during my DJ residency at the midtown Manhattan transsexual sex worker club "Sally's II" in 1990 and '91, the fact that the majority of transgendered people there were engaging in hormone therapies and surgical alterations often led to the judgmental ostracization of non-medicating drag queens, such that I was ashamed to out myself as transgendered within the heart of a transgendered safe-space. Rather, I came to work in male drag, a habit which continues to influence my wardrobe when appearing as DJ Sprinkles.

When I do wear women's clothes - particularly within an employment context - my general approach is to downplay elements of camp, and dress in relatively standard apparel. Beyond safety concerns related to drawing excessive attention to oneself in potentially homophobic and transphobic environments, this is also a strategic rejection of the stereotype of the flaming queen, and the demand upon transgendered people to submit ourselves as fodder for entertainment and spectacle. This resistance to performance plays a large part in my electroacoustic audio performances, which seek to infiltrate media festivals and other events with deliberately boring and unsatisfying experiences for the audience, organizer and performer. In fact, if I feel my invitation for employment is rooted in a fetishization of my status as a transgendered performer, and the promoter seems overly enthusiastic about my appearing in female drag, I will deliberately appear in men's clothing. Although this may be taken as personal betrayal (by not being "true to oneself"), contractual betrayal (by not fulfilling an employer's expectations), or even communal betrayal (by failing to show a particular kind of "transgendered pride" that conquers "the closet"), I feel it is imperative that people question their expectations around transgendered bodies - particularly since the primary condition of transgendered life around the globe is not celebratory self-actualization, but secrecy and the repressions of the closet. In the end, for transgendered people to only be granted public audience when playing the role of a campy snap diva who appears to her straight audiences as having transcended the troubles of life, in effect absolving dominant culture of it's crimes by persisting despite domination, is the ultimate manifold betrayal enacted upon and enacted by ourselves.

At a personal loss for what to do, the tyrannical demand to "look fabulous" in drag (or conversely "over the top grotesque") has pushed me to try to publicly discuss the turmoil of being born with a penis, commonly dressed in men's clothing, yet still transgendered identified. Since men's clothing seems to offer a visual reconciliation with dominant cultural expectations around my body (which grants a degree of personal safety, yet betrays my political and cultural outlooks), and since this reconciliation is denied me when dressed in women's clothes (which also revolve around a patriarchal image of femininity that betrays my political and cultural outlooks), clothing ceases being about self-representation. It is reduced to a manifestation of the dissonances between identity and experience. This, for me, is a valid starting point for cultural investigation around clothing. But it is vital to remember within this formula fashion is not a facilitator of investigation, but an enabler of that which is under scrutiny. Fashion is the medium through which I find my body granted and robbed of privilege.

It was in the project Trans-Sister Radio, an electroacoustic radio drama commissioned by Hessischer Rundfunk in 2004, that I attempted to discuss the legal implications and risks of these privileges as they apply to transgendered mobility, internationalism and migration. In particular, I questioned the various relationships between gender transitioning, spousal visas and marriage as sex work; all of which were very scary issues for me to discuss openly at the time since my spousal visa in Japan was pending renewal, and I had not yet received permanent residence status (which grants a bit more legal independence and expressive flexibility). And, as if to demonstrate the very notions of privilege at issue, it was a year later when the follow-up broadcast The Laurence Rassel Show found itself cancelled for favoring the ever unfashionable term "feminism" over the trendiness of "transgenderism."

In my opinion, fashion - like the visual arts and music - seems to lack any potential for repoliticizing the terminology of anti-traditionalism and revolution that have been rendered numb by over-saturated industrial ad copy. And, as with other media industries, the root of this impossibility seems to be its participants' ideological disconnection from the systems of violence through which the fashion industry constructs and perpetuates itself. Even when social issues do arise in the fashion world, they are so over-stylized and steeped in centuries-old Christian aesthetics of martyrdom - those same aesthetics which transform a bleeding Christ on the cross from an image of tradition-shattering horror to one of sublime and pacifying beauty - that we find ourselves hypnotized by the sensuality of our oppressions, even longing for their familiarity. I am not against sado-masochism (although I admit I find it personally boring, childish, and lacking the cultural potential proclaimed by Foucault and the rest); and within a Judeo-Christian heritage you would be in the minority if you were not to find grace in misery - it is the core of our social pacification and domination. But I do feel compelled to protest when the fashion industry - any industry - claims to stand at the vanguard of a culture (vanguardism being a ridiculously transcendental claim in itself), and with a peoples' best interests in mind, yet perpetuates the miseries of those people consistently and without fail. When our attempts at resistance are seamlessly and invisibly transformed into marketable trends, this is a mark of complicity, and not of success. In this way, "out of order" fashion is simply a very elaborate cultural sedative granting the illusion of mobility within a rigid socio-economic system.

I am speaking, of course, as someone who faces similar limitations working in the audio marketplace, where we all know "alternative music" is nothing more than a marketing ploy. And we all know from personal experience how fashion and music are interwoven as means of self-identification and socialization, functioning as signals to attract and repel those around us. So I am not speaking from a position of superiority, or higher understanding. I am speaking as a dupe; a sheep infected with the same diseases of desire as the rest of you. It is from this common base that I wish to say I do not believe we can transform industry into something liberating, any more than I believe transgenderism allows us to transform our bodies into something liberating. Culturally, our liberation is not up for negotiation. Socio-economically speaking, capitalism relies upon our exploitation. And, of course, the fashion industry is notorious for it's systematic reliance upon sub-standard work policies, ranging from unpaid internships to Third World slave labor. Even the heralded "sweat free" factories of Cambodia only pay workers €20 per month (averaging 25% overtime).

Rather than fantasizing about liberation through industry, industries need to be de-essentialized/denaturalized/dereified as vehicles of moralistic principle, and seen as material processes - not ideological processes - so that we may restructure our ideological relations to those material processes. This includes demystifying "out of order fashion" as "a matter of principle," so as to better understand its propagandistic functions within a larger dominant cultural context - because, like so many alternative culture industries, the principles being served are rarely those we wish them to be. In fact, they most often betray us. These ideological associations between industry and liberation, industry and leadership, industry and our social potential for realizing an inherently flawed concept of benevolent power, all need to be dismissed before we can even begin to think about the true topics we claim we wish to discuss. As a labor base enslaved to one industry or another in the service of domination (economic domination, national domination, global domination), what is first at issue is what kind of slaves we choose to be within those dominant systems.

Refuse to attach your dreams to the fashion industry's attacks on taste, even if you support them with your labor. Do not be ideologically seduced by the martyrdom of impractical clothing, as it is ultimately a sacrifice to the cultural Father. You may design it, you may manufacture it, you may sell it - but realize you do so as a slave, a dupe, a sheep, kissing the ass of H&M or whatever major company you or those around you pray will pick up on your patterns - hopefully after, and not before, you copyright them. Feel the weight of being forced to kiss this filthy, rotting ass. Breathe it in. Taste it. Vomit from it. Because it is only from the necessity to end the unacceptable that our principles take on importance; and even so, only for a moment.

We all know principles are contextual - not rooted in "universal human truths," but in times and places - and in this sense they strike me as very poorly served by dreams of mobility or freedom. Those may be things we desire on a subjective level, but they are not at the root of our urgency nor a basis for social action. The institutionalization of principles, including "out of order fashion" as a matter of principle, is ultimately an extension of the domination we claim we wish to diminish. If, indeed, one's interest is in a type of cultural transformation which goes against domination, and which seeks to minimize the violence of current social praxis, then it seems imperative to actively and critically address issues of fear, violence, and culturally mandated hypocrisy. I am not talking about designing a season on the theme of domestic violence, or ribbon campaigns, or anti-fur advertising campaigns featuring nude fashion models, or other forms of political profiteering. There is always a cultural surplus of that sort of propaganda, which is about as socially engaged as choosing to pay with a high interest credit card because your credit company, which systematically bankrupts millions of people annually, will donate a fraction of a percentage to some mainstream charity hemorrhaging with administrative overhead. I am talking about recognizing one's own placement in a moment of crisis from which all directions are traps, and to then leave oneself vulnerable to crisis. As a member of the audio-activist collective Ultra-red recently wrote me, "once confronted with that crisis (the crisis of one's alienation), then one either enters into it to see what can be learned, or one retreats (aggressively) to the very modes of being that affirm and nurture the alienation."

One of the peculiar difficulties of working within academia and the arts is that the theme of principles is so omnipresent, yet simultaneously entrenched in those modes of being which foster our alienation. As systems, they are not unlike religion. In fact, the histories of higher education and the arts are entwined with the history of monasteries, convents and cloisters. As a result, we find that the language that emerges from and sustains these judgemental social systems is ass-backwards, and obsessed with the illusion of providing spaces devoid of judgment. A neurotic desire to believe our institutionalization is non-judgemental stops us from entering deeper into our alienations within these rigid systems, since giving our alienations visibility and conscious identification without claiming to know a means of resolution becomes tantamount to failure. Of course this is, in itself, judgmental and reflects the trauma of an educational system that demands we pass to advance, and punishes failure.

Based on my own experiences, I find that when these hypocrisies underlying our gatherings are directly called into question, members of the audience invariably arrive at two reflexive reactions: first, they ask what they are to do (or more specifically, what I want them to do); and second, they insist upon filtering what I am saying through familiar and naturalized concepts of hierarchy until it can only be heard as one form of authoritarianism wishing to replace another. The first reaction of wanting to be told what to do is clearly symptomatic of our immersion within systems of domination such that we can only conceptualize solutions to their oppressions as coming to us in the form of directions. The second issue of insisting that all discourse be reduced to, and judged in relation to, authoritarianism strikes me as a self-defensive impulse intended to preserve the ideological processes that enable one's "normal" social functionality within existing systems of alienation, rather than making oneself emotionally vulnerable to the alienation itself. In identifying these judgments as preconditions of my freelance employment, my chief difficulty is in complicating notions of being open to vulnerability without "openness" being reduced to "anything goes" apathy. How can I present the fact that I find no agency within this employment system - a competitive patronage system many of us here today are contractually dependent upon to one degree or another - as a means of connection and joint investigation with you, as opposed to my being dismissed as a defensive, antagonistic, and ungrateful bastard robbing an academic budget you feel should have been spent differently?

These are the traps before us at this moment. The traps of this professionally crafted response, by which I am simply doing what is expected of me as an employee. It is a performance - a drag show - contributing to an image of free speech and an open exchange of ideas within the framework of this symposium organized by the Fine Art and Design Department. In fact, the more vigorous my critique the more it affirms the graciousness of its object for facilitating said critique. Everything I do or say boils down to "out of order symposia - a matter of principle." Do you see the traps I am talking about? How our personal intentions, our principles, are irrelevant when everything can be reduced to a performance - a reduction that is inevitable when our actions and histories are catalogued and archived by the very systems at issue? These traps are shared by "out of order" fashion in its attempts to conflate runway attacks on taste with political resistance, as its metaphors of struggle become reified and mistaken for struggle itself. My self-sacrificial gestures here today - my apparent openness and vulnerability as a result of risking to say unpopular things in this setting - are not dissimilar to the martyrdom resulting from the development and production of "impractical" and "unwearable" fashion. This is our shared crisis that simultaneously unites and alienates us.

I believe it is vital that we shine light on these aspects of alienation, negativity, impossibility... because to only emphasize the authoritarian "leadership" potential of us and our industries results in a distorted sense of community which all the more excludes and conceals the oppressions binding us together. Such culturally self-serving discourse is the definition of propaganda. It clouds us with the idea that we are assembled here out of "free will" rather than out of class requirements, job requirements, or simply the pressure to keep up with trends. If we cannot confess to these most basic power dynamics underlying our assembly here today, how can we ever hope to produce more complex analyses of our relationships? Although my specialty is not fashion, the language in the English description for this symposium strikes me as symptomatic of the near fascistic enthusiasm and rivalry forced upon those employed in fashion industries:

- As an element of a new and glamorous Celebrity Culture, fashion is one step ahead of other trades and the new-fangled concepts of Creative Industries. [...] Fashion leads the way: Fashion designers, as well as fashion photographers and performers always have been on a quest for disruptions of perception and of production processes. The so called "bad taste" turns glamorous and leads the way for fashion, while the abolition of dress rules turns into a fashion label. Fleeting occurrences and breaches of the established order become the norm. The deviant becomes the new rule.

I know many of you hear these words as I do - a tragic ode to our cooptation, a love poem to capitalist systems of domination, ad copy sound bites defeating content. I feel you choking down your reactions to such positivist language like so many atheists silenced by a swarm of evangelists. I understand that social and economic factors make it so you cannot force up your reactions here and now, but can only bring them up later in private like so much bulimic waste. It is you to whom I am directly speaking when I say, as your sister, I am using my employment here today to bring you a message: You are wasting away. Digest or die.

| Endnotes |