|

terre thaemlitz writings 執筆 |

|

GLOBULE of NON-STANDARD An Attempted Clarification Of Globular Identity Politics In Japanese Electronic 'Sightseeing Music' - Terre Thaemlitz |

Summary

This article attempts to identify trends in non-academic Japanese electronic music related to the representation of identity issues including gender, sexuality, ethnicity and race. Simultaneously, it attempts to point out limitations in Western identity politics which complicate the identification and clarification of such themes. In particular, the Western desire to define cultural diversity through a multiplication of distinct identity constructs is contrasted with Japanese aversions to images of factionalism or political affiliation. It is postulated that the "Globular" identity politics found in Japanese electronic music suggest ways of thinking around Western ideological conundrums such as the tendency to use terms of "equality" (a notion of similarity) when negotiating for communal "diversity" (a notion of dissimilarity). This extends to current attempts at diversification among academic and commercial digital audio producers.

Best known in the West as the founder and most "experimental" member of Yellow Magic Orchestra [YMO], Haruomi Hosono's role in Japan has been more of a mentor than a musician. Between his Kraftwerk-like clarity of vision (not to be confused with a Kraftwerk-like linearity of sound) and a collaborative production breadth comparable to that of fellow bassist Bill Laswell, most of today's Japanese electronic producers still confess a debt to Hosono's broad influence. In 1984, he launched a multi-media series comprised of Non-Standard Books, Non-Standard Music and Monad Music. The self-billed "pre-first edition," Making of NON-STANDARD MUSIC/Making of MONAD MUSIC, was a multi-media release consisting of the paperback book GLOBULE (a combination of text, photography, illustrations and comics), and a vinyl 12-inch single with one side produced in the NON-STANDARD vein (Hosono's self-declared "World Famous Technopop" production style), and the other side produced in the MONAD vein (a hybrid of commercial background music [BGM], Ambient and Music Concrete). On the final pages of GLOBULE (or, on the opening pages if you open the book Western-style with the spine to the left) was a manifesto written in broken English that introduced the West to several important themes related to Identity construction in the works of Japanese electronic music producers: "GLOBULE," "NON-STANDARD" and "Sightseeing Music." That short text is reproduced here verbatim and in its entirety:

- GLOBULE (Statement of Purpose)

Haruomi Hosono has started a new label 'NON-STANDARD', 'MONAD'.

This 'Making of NON-STANDARD Music' is a pre-compilation for this label and is produced as the pre-first edition. NON-STANDARD BOOKS [GLOBULE] is not added as an appendix, this has been planned as an independent media for the idea and the expression of Haruomi Hosono, and of the other artists produced by him, and this will be coming out regularly.

A word 'NON-STANDARD' is derived from NON-STANDARD ANALYSIS in modern mathematics. As represented in Fractal Geometry, modern mathematics or modern science suggests a means to converse with Nature not disorganizing it to construct culture as has been happening up to the present. Haruomi Hosono implies in the word 'NON-STANDARD' not a conventional science but a spirit of new science. In other words it can be another naturalism (SHIRAKABA-HA in Japan) in this hi-technology society. NON-STANDARD therefore includes various ideas and expressions. Haruomi Hosono is at present under-taking 'Sightseeing Music' and this is one of the expression. NON-STANDARD also develops the ambient music started by Brian Eno to a global level and to converse with and respond to a dispatch from the earth. This is part of the idea.

Now we would like to comment on this publication, GLOBULE. Firstly, a title of this book; a word, GLOBULE came into his mind inspired by monadology on the earth and on fractal, and he has given it a characteristic element. GLOBULE looks as a creature or machinery, yet it is not. It exists in the middle of everything, in a very ambiguous zone. That is, GLOBULE has become part of a character of NON-STANDARD. Various types of Japanese talented creators, comix/artists and SF writers contribute to this publication over this mysterious 'existence'. Some of the contributors expressed in the form of comix, a diagram of GLOBULE, its history of evolution and when and where it had encountered the mankind. It also includes a document on mankind's close encounter with GLOBULE.

Haruomi Hosono also called GLOBULE 'seeds of stars'. It will grow and stay within a mind of Japanese hi-tech kids and it will be the real NON-STANDARD mankind that will try to dialogue with the earth.

(Hosono 1984: 175-176.)

| 1 Several of my own projects, such as the album Fagjazz and the Sanriot design project (www.sanriot.com), have drawn parallels between Engrish and Queer discourse as both share a linguistic strategy of reappropriation and recontextualization. For example, the act of self-identifying as "Queer" itself represents an attempt to disarm Homophobic terminology through alternative usage, while simultaneously relying upon the term's negative associations as a reminder that sexual behaviors are always framed by the cultural codes of the societies in which they occur. The contemporary notion of "Queerness" is largely a critical response to the Hetro-/Homosexual binarism, through which the social regulation of sex is no longer a matter of behaviors (ie., the possibility of an individual's choice to partake or reject certain behaviors), but one of biological imperative (all persons being "born" Lesbian, Gay or Straight with no personal agency and zero tolerance for mobility between identities). |

Native English speakers are immediately struck by the text's ambitious yet awkward use of grammar and vocabulary. This sort of misuse of English in Asian media ("Engrish" as it has commonly come to be known) is a common sight for anyone familiar with Asian music packaging, not limited to releases from Japan. Engrish thrives in Asian markets where people with little or no English ability are exposed daily to advertising and other media featuring English letters and vocabulary. It can be seen and heard on television, films, publications, and even daily conversation. The majority of Engrish communiques favour an English word's nuance over its specific meaning, and can even prescribe entirely new definitions contrary to those used in the West (for example, in English a bank sign reading "No Loan" would most likely mean "no loans are given at this bank," but in Engrish it refers to a loan with a zero percent interest rate, or "non-interest loan"). Certainly the linguistic stylisation of Engrish relies upon a degree of fashionability and fetishism both in indigenous Asian markets (invoking fetishized images of the West) and foreign markets (playing on fetishized Orientalist images of the East). As I have mentioned in other writings, it is in these ways that Engrish, as a Capitalist marketing strategy, parallels the Global Music Marketplace's general disinterest in representing contexts of production in favour of hollow imagery (eg., World Music). Conversely and perhaps of greater interest here, Engrish as a social phenomenon takes on political importance by transforming a colonial tongue into a new and indiginous system.1

The vagueness of the Engrish used in the "GLOBULE" manifesto - that very vagueness which is most likely making you question my citing it as an important document - is perhaps the most fundamental element of Identity construction in Japanese electronic music: Identity as a body of content which "exists in the middle of everything, in a very ambiguous zone." Identity is considered simultaneously deliberate and accidental in its inception and reception. It is both bound and liquefied by the limitations of one's cultural visions and communicative abilities. The individual's form exists between forms. Therefore, the notion of a "social movement" only takes shape while refusing clarificationノ a GLOBULE marching a discursive path. Of course, this notion of social movements taking shape through an obfuscation of form is common to Western activism as well. For example, the American Civil Rights Movement and the contemporary notion of an African-American identity can be defined as the result of refusing the clarity of previously traditional roles for Blacks in America. The radical difference is that Western identity models typically aspire to a model of group autonomy (eg., defining a "Gay Experience," the singularity of which ultimately acts as a form of social homogenization rather than diversification), whereas Globular strategy does not presume the potential for communal autonomy nor Western Individualist self-determination.

| 2 Starting with Eno's 1975 release Discreet Music, Ambient music was originally discussed in relation to Modernist and Sartonian themes of paralysis and illness. Eno's liner notes to Discreen Music explain how he first conceived of the project when confined to bed by an accident and, unable to reach the volume control on his stereo, was forced to listen to a record of 18th century harp music at the edge of audibility. Hosono's suggested inversion of Eno's introspective model of Ambience, by taking it from the Individual to the Global, was later realized in the West during the late '80s and early '90s through the group listening environments of Ambient "Chill Rooms." It has since been pushed further by producers and groups such as Ultra-red, a Los Angeles based audio action collaborative. Drawing upon Jacques Attali's assertion that music's order simulates social order, and its dissonances express marginalities, Ultra-red works in conjunction with grass-roots organizations to strategically manipulate the sonic ambiance at political rallies, civic meetings, and other politically charged environments. |

Whereas the launch of a company is usually an attempt to crystallize a corporate identity, the launch of Hosono's media series under the dual names "Non-Standard" and "Monad" announced works representing a multiplicity of approaches and artistic identities. Similarly, describing the first release as a "pre-first edition" represented a further decentralization of the media series' historical origin - ensuring that the next and inevitably "first" release emerged from a pre-existing context rather than being the origin of a species. Much like fractal geometry, in which a "random attractor" exerts influence over the non-linear progressions of fractals, Making of NON-STANDARD MUSIC/Making of MONAD MUSIC was conceived as a GLOBULE around which future producers could use various media and genres to build upon and repel one another. One such example of the push and pull of artistic influences was Hosono's objective to "develop the ambient music started by Brian Eno to a global level and to converse with and respond to a dispatch from the earth." To the best of my knowledge, this statement was the first documented postulation to derive communal strategy from Eno's traditionally isolationist theory of Ambient music - a radical concept that would go unnoticed in the West for another half decade.2 While the phrase "to converse with and respond to a dispatch from the earth" has rather lofty and Hippy-esque overtones (which are also important aspects of Hosono's work), within the context of the book GLOBULE "earth" takes on more materially grounded connotations of social habitat and global marketplace. Therefore, calling for a response to a "dispatch from the earth" also implies actively engaging cultural ambiance, and paying attention to social workings that typically go unnoticed.

|

3 Japan's current ban on visual representations of genitalia is a prime example of such trend-based politics. The current restrictions are the result of a series of ever-escalating lawsuits from the 1980s between the Japanese government and the publishers of Photo Age magazine. Photo Age featured Nobuyoshi Araki's candid photo essays of Japanese sex workers, a community that was then booming through the financial and cultural excesses of Japan's bubble economy. Somewhat similar to the American government's response to Homoerotic photos by Robert Mapplethorpe, conservative elements of the Japanese government used Araki's photos to debate definitions of pornography, and began placing restrictions on what could and could not be portrayed in photographs. With a bit of good humor and overconfidence in both the freedom of the Japanese press and an artist's right to self-expression, Araki and Photo Age took the anti-censorship limelight, responding to each new legislation by pushing it to the limit. For example, after it was deemed illegal to directly show genitals, Araki only photographed pubic hair. It then became illegal to photograph pubic hair, after which Araki photographed women with shaved genitals that were then concealed by manually drawing pubic hair onto the photos. And so on, until legal costs forced Photo Age out of business and Japan was left with today's excessive censorship laws. (In recent years they once again made it legal to show pubic hair, but this change occurred quietly and there has been little to no additional movement around easing current censorship laws.) 4 In Japan, dolls are traditionally placed and statically observed, rather than actively played with - a fact which caused unexpected marketing complications for the makers of Barbie when first introducing their Western 'action' doll in the Japanese marketplace. (It is also worth noting that traditional Japanese dolls are played with by boys as well as girls.) This cultural difference in interactive relationships is important when considering dolls as social conditioning devices for children. While a Western analytical approach might quickly conclude the Japanese use of dolls urges passivity and submission, it is more informative to consider the Japanese model in relation to actions of self control, situational control (the power of the arranger over that which she arranges), and sculptural stoicism. |

In Japan, where Leftism is traditionally unidirectional and still associated with antiquated images of extremists or terrorist organisations such as the Nihon Sekigun (Japanese Red Army), many Left-ish Japanese producers prefer political expression through the omni-directional momentum of Globular artistic strategies. In other words, allowing their actions to be perceived as "artistic expressions" subject to the ambiguities of art discourse makes it difficult to identify a coherent social agenda. Unfortunately, this clouding of thematic intent often results in a conflict of interest between a producer's desire for cultural change, and a refusal to be seen as taking sides (let alone define what those various sides may be). It is a potential stalemate similar to that arising from Western Liberalism's terminal inability to reconcile the imbalances of "special needs" with "social equality" - both of which are considered key elements to Western models of cultural diversity. On the other hand, the inability to quickly identify a social agenda helps Japanese producers who are typically at the fringe of economic viability from suffering the silencing consequences of further social and financial ostracism. In Japan, radicalism of any kind is best received when introduced as a non-threatening fashion trend. We are left with hollow images of diversity that mimic the social workings of Japan's dominant cultural system which, when cornered (and unlike the West), has few qualms about admitting its disdain for difference or change.3

Within the field of Gender Studies, we find images of Japanese women who are simultaneously comforted and frustrated by the all-too-clear oppressive demands of conventional Japanese women's roles - a theme appearing regularly in the works of the mid-80s performance group After Dinner featuring Haco (Haruko Mizoguchi). For example, in their debut album After Dinner, the song "Soknya-doll" draws associations between the internalisation of feminine role-playing with the traditional children's pastime of situating dolls4:

- Hey, doll

I make you sit down there

I am free of care

Hey, doll

You sitting in the empty room

I feel reassured

Falling deeper

A pale shining soul

Whose soul, Mine, or Doll's

I don't know

Hey, doll

You sitting in the desolate room

I am out of danger

Say, doll

As it's my first arithmetic

'Hey, you, a sham

I'm a passing mirror'.

(After Dinner 1983)

The lyrics open with images of the doll owner's freedom and control. However, the doll's words in the closing lines, "'Hey, you, a sham - I'm a passing mirror,'" identifies the doll as a reflection of its owner, challenging the authority of the girl situating it, as well as calling into question the cultural positioning of women in general.

Disbanded in 1987, today After Dinner remains more known in the West than in Japan. However, contemporary Japanese producers have recently "discovered" After Dinner's work and begun discussing its importance - including the importance of why it has remained largely unknown in Japan until now. After Dinner was originally formed as a collaborative performance group consisting of engineering and audio students based in Osaka. Haco, who assumed the conventionally "disempowering" image of female lead-vocalist in an otherwise disproportionately male group of musicians, was in fact the key composer and a technically trained engineer. Still better known in the West than in Japan, Haco continues to work as a solo artist, releasing on such labels as ReR (UK) and Tzadik (John Zorn). In addition to her renowned improvisational works (one recent series combined vocals with electronic feedback from microphones placed inside small domestic items such as a Japanese tea kettle), she is also the founder of Hoahio, an all-women's Experimental electronic ensemble with occasionally rotating members that have included Sachiko M and Michiyo Yagi. Yet in typical Japanese fashion Haco is reluctant to directly identify any of her works with a Feminist agenda. Despite how her activities might be perceived in relation to Feminism, for Haco a project such as Hoahio is actually motivated by an attempt to create a 'safe space' where women can produce Experimental music without concern for their identities as (Japanese) Women Producers, and without concern for fulfilling any Feminist expectations. It is a contradiction of autonomy and community-building. Autonomous through its attempted separation from norms of reception around all-women collectives. Community-building through its gathering of individuals, and rotating membership. It is a NON-STANDARD attempt to reorganise oneself in the wake of cultural disorganisation. Another SHIRAKABA-HA in this hi-technology society.

According to the conventions of Western Identity Politics, a "safe space" (be it for people of a particular gender, race, culture, sexuality, etc.) is typically perceived as a place of resistance to the unsheltering conditions of Dominant Culture. However, the history of "safe spaces" has just as well worked toward the preservation of systems of power (ie., membership in an elitist country club, popular religious affiliations, university affiliations, the family unit, etc.). It is through these contrary implications of "safe spaces" that some Japanese women producers, such as the Berlin-based Hanayo, find empowerment by celebrating the male-free (yet patriarchally dependent) confines of Girl Culture. Inhabited as much by women as girls, Girl Culture constitutes that hyper-sexualized-yet-sexless realm of Japanese society dedicated to "girlish" fashion, music and media (key words: cute, happy, best friend). Within this sphere, the only images one finds of men are sexually non-threatening androgynous boys... or better yet, women posing as Prince Charming.

Self-defined as a "Mommy," Hanayo is first and foremost concerned with finding ways to expose her daughter to the mono-gender comradeship of Girl Culture, a system lacking in Germany. However, for the purposes of this publication she is perhaps best defined as a "media personality." Hanayo's professional activities span eclectic vocal performance (typically encouraging a deliberately puppet-like role in her collaborations with such hard-edged male electronic producers as Merzbow, Panacea and The Black Dog), multi-media gallery installations and photography. A formally trained Junior Geisha, Hanayo moved from Japan to Europe at the end of the '80s, where she became a cause célèbre within various post-Punk and trash-culture scenes, as well as in the popular media. Hanayo was one of the first female Japanese Experimental musicians to trigger the now formulaic trend (read: fetish) among Western music promoters to organize performances by "tiny Japanese girls making big noises." Perhaps in keeping with the discipline of her Geisha training, or perhaps with the deliberate placement of a Japanese doll, Hanayo situates herself in such a way that her only apparent act of control is the initial act of self-placement - a strategy which has drawn suspicion and criticism in relation to her perceived lack of concern for issues of gender, race and ethnicity. And she could care less. In keeping with a Geisha notion of willingly and unashamedly (yet silently and graciously) seeking sponsorship within patriarchal systems, Hanayo is unconcerned with Western models of artistic autonomy and individualism which only serve to cloak the systems of dependency within which all persons operate. As an artist producing work in a Western context, her projects are most informative when recognising the ways in which her ambivalence toward "progressive" political propriety so thoroughly frustrates Western models of empowerment. Given the strength of preconceptions around Geisha imagery (in particular, female subservience and/or sexual servitude), the desire is to simply define her work in relation to gender issues, when in fact its punch rests in much broader, GLOBULAR issues of irreconcilable cross-culturalism.

Admittedly (and as with much work from Japan and elsewhere), Hanayo's projects lack the critical focus one hopes to find in any work associated with that buzzword "diversity." However, the result is not a failure within her work, but a realization of the Western audience's critical expectations around the production and reception of "Experimental" works by traditionally marginalized producers. In other words, it becomes apparent that producers such as Hanayo are expected to produce works which break through cultural processes of marginalization and achieve a degree of "visibility," while at the same time not capitulating to processes of tokenism associated with the act of crossing such cultural borders (ie., selling-out one's heritage, gender, race, sexuality, etc.). In this way, we see how the notion of "self-empowerment" is often twisted so that marginalized producers effectively become responsible for negotiating the terms of their own marginalization. By visibly allowing her career to be as much a result of tokenism as diversification, Hanayo rejects personal responsibility and places it back upon depersonalised cultural processes of marginalization. Furthermore, the Western demands of self-empowerment (ie., multi-cultural identity constructs which uphold Western liberal ideals of Feminism, Racial Equality and Individualism) are complicated by her movement between both conservative and deviant models of Japanese Womanhood. For example, in the West there is an essentialist desire to respect her use of traditional Geisha imagery as a means of respecting Japanese culture in general, despite potential anti-Feminist interpretations. At the same time, her contrary punkish behavior points toward a critique or disavowal of those traditions, but in such a way that the codes of "respecting cultural diversity" prevent Westerners from joining that critique of Japanese culture, let alone understand its terms. Hanayo's public appearances are culturally detached from Japanese culture, detached from Western culture, yet operating culturally within Japanese culture as a representative, and within Western culture as a resident. Ultimately, what one may construe as her points of critical "failure" are inextricably tied to (and justified by) models of Western- and self-imposed otherness. Her model of cross-culturalism does not aspire to conventions of "celebrating diversity." Rather, it positions her amidst the problematics of a Western public's tolerance of her gestures - a culture's ability to tolerate foreigners.

A chance to clearly recognize the limitations and demands of one's own cultural ideology, such as that offered by Hanayo's work to those of us with at least one foot in the Western Cultural-Criticism camp, is always rare. If post-Modern philosophy emerged from a critical deconstruction of Modernist philosophy's illusory ability to transcend the culture it attempts to critique (ie., the Modernist proponent looking back upon a cultural valley as viewed from the peaks of the vanguard), then the post-Modern producer never forgets her placement within that which she critiquesノ a vital admission if ever there was one (and perhaps overwhelmingly obvious with historical hindsight). However, one of the dangers of post-Modernist identity politics is a myopic view of society from its core, as expressed in demands for global cultural diversity to assume regionally (Western) "progressive" forms (eg. the assumption that Western Humanism's basic assumptions about human rights are universally translatable and acceptable as a basis for global civil rights). Realistically, even within Western cultures, living according to these ideals is simply not compatible with the conservative social requirements of making ends meet.

For example, despite a Transgendered person's personal views on gender conformity, there is a cultural demand to represent oneself through the popular binarism of Female/Male gender imagery. Whether working in an office or shopping in the grocery store, she must appear as a woman and he must appear as a man in order to avoid being subjected to emotional, physical and economic abuses. (It is important to note that the functional degree of cross-gender passability required for basic employment is only achieved by a minority of Transgendered people, and this ability usually diminishes with age.) While the gesture of gender transformation has wildly dramatic connotations in most cultures - conjuring notions of ultimate physiological and cultural deviance - the aspired end result is often disappointingly conventional and non-threatening. Jim simply wants to be a woman. Jane simply wants to be a man. They typically do not aspire to being mutants. It is not so much an attempt to rewrite society, but simply a manifestation of the individual's desire to eliminate conflict by conforming to cultural norms one feels comfortable with - the same plea for tolerance advocated by countless Lesbians and Gays who insist they are "just like everyone else." Transgendered communities seem to present a perverse desire to capitulate to the demands of those same Dominant cultures from which they are ostracized to the cultural periphery - a situation not uncommon within the realm of identity politics. However (and like many sub-factions of identities), at that periphery they experience confusing isolation at the hands of other ostracized communities. This extends to the historical antagonism between Women's Rights movements and Transgendered Rights movements.

Transgendered communities are typically seen by Women's Rights advocates as anti-Feminist for perpetuating traditional and conservative gender role models. For example, the types of Women most people think Male-to-Female [MTF] Transsexuals aspire to become are considered politically regressive and rooted in conventional patriarchal imagery (in other words, they're too Femmy). This makes political alliance between many Transgendered people and Women's Rights advocates difficult at best. Similarly, the needs of Transgendered communities are traditionally marginalized and rejected by Lesbian and Gay Rights movements as well. Again critical attention is usually focussed on Male-to-Female communities, whose Drag Queens make for wonderful entertainers (and clowns at the front or back of Pride Parades), but embarrassing political bed partners. As a result, Lesbian, Gay and/or Women's Rights labour organizers and others repeatedly refuse to advocate for the protection of Transgendered rights, despite our existence and crossover in many spheres of culture. As a Transgendered and pansexually Queer producer, a great deal of my own work has focussed on these cultural dangers of gender- and sexual-essentialism both within and without Transgendered, Lesbian and Gay communities. These issues are further complicated by various treatments of Transgenderism within People of Color communities.

With regard to this breakdown of cooperation amongst those inhabiting a cultural periphery, there is an odd similarity between the Western dismissal of Transgendered identity issues by Women's-, Lesbian- and Gay Rights activists, and the sceptical reception of Japanese identity issues by other People of Color communities in the West. Japanese immigrants typically lack the "racial abuse potential" associated with many other Asian/Pacific Islander communities. Japanese people in the West are not so much considered "disenfranchised" as simply "not in the majority." This difference in perception presents a radical break from the power formulas ruling conventional Ethnic and Racial identity politics. Much as Transgendered people are often rejected by the communities with which they seek alliance, Japanese community organizers and cultural activists are often rejected by other Asian and Pacific Islander organizers with more immediate claims to oppressive material conditions. The Japanese community is undesirably associated with the core of Western Dominant culture _ an association furthered by memories of the tragedies of Japanese militarist expansionism prior to World War II, and economic expansionism afterward. Such antagonisms at the cultural periphery result in a frustration of the concept of "otherness" found in conventional identity politics. It is not so much that conventional rules of otherness do not apply, but that the cause and effect of such rules seem to take different courses and involve unknown influences. The Japanese community is seen as dissimilar from other Asian communities at the periphery, and therefore "non-other" within the dichotic confines of Western "dominant/other" identity politics _ hence it becomes associated with that which is "dominant." Their social displacement is less likely to be equated with "refugees" than with "tourists" - the strongest stereotype of Japanese people still being the camera wielding vacationer.

One of today's few music groups openly addressing all of these identity issues (gender, sexuality, ethnicity, race, migration and imperialism) is the UK-based Japanese Lesbian duo Frank Chickens, featuring Kazuko Hohki and Kazumi Taguchi. (Perhaps unbeknownst to some, the first two albums featured extensive programming and arrangements by musician and author David Toop.) As with many Japanese women who emigrate to the West, Hohki and Taguchi moved to the UK in order to escape the stifling lifestyle restrictions placed upon Japanese women. However, within the UK they found themselves confronted with an entirely new series of prejudices, fueling songs such as "Yellow Toast," from the album Get Chickenized:

- Oh we love England green and free

So we flew across the sea

To the land of trust and sympathy

We think this is the place to be

Oh we like being yellow nips

Because you all think we are hip

But if you think we are so wise

Why don't you look us in the eyes?

Japanese mystery is convenient

It makes you think we are content

You think we are full of Zen

But we prefer lots of yen

All de men love de yellow woman

All de men love de yellow woman

You think we are born to sin

And yellow sex is just amazing (vomiting sound)

If you are happy with illusion

And you want to have no conclusion

Then we are stupid little Japs

And you are splendid English* chaps

Why don't you look us in the eyes?

*substitute your nationality here

(Frank Chickens 1987)

The immigrant carries culture like so much travel baggage filled with ones cherished belongings, counterbalanced by the memory of those things left behind which were unwanted or too big to carry. The Frank Chickens' baggage is filled with Japanese pop culture, twisted into tools to combat oppression. For example, the song "Mothra," from their 1984 debut full-length album We Are Frank Chickens on Kaz Records, uses the Japanese monster film of the same name as a metaphor for their own quest for social mobility in both Japan and Europe. In the film "Mothra," The Peanuts (a famous Japanese pop music duo consisting of twin sisters) play miniature native women living on a Pacific island guarded by Mothra, a gigantic moth. The women are captured by Japanese investors, and forced to sing in a circus. They repeatedly sing a song called "Mothra," which is eventually heard by the monster who then comes to rescue them, destroying the city in the process. The members of the Frank Chickens identify with those hostage miniature women from a Pacific island. The women's miniature stature compared to their captors symbolizes the sense of cultural powerlessness and disenfranchisement experienced by the Frank Chickens as women and Lesbians. The reference to body size is also typical of the Frank Chickens' recurrent invocation of physical differences between Japanese and Europeans that are the basis of many racist expressions. The kidnapping Japanese captors represent the confinement of Japanese Dominant culture, as well as raising issues of colonialism and migration. In this way, the Frank Chickens' song "Mothra," like that in the film, becomes a call for cultural transformation in the form of destructive winds born of monstrous wings... the flight of the emigrant.

A key aspect of the Frank Chickens' work is their Globular launch of critique from all sides, as critical of the land they left as the land they live in. Issues of Japanese colonialism and inter-Asian race relations appear frequently in the album Get Chickenized, such as in the song "Island Inside Island" which specifically refers to the Japanese conquest of Okinawa:

- We think they belong to us

They think we came from them

Water between us never change

We think we are the same

They know we are different

Different hair-styling

And different smiling

They want to keep their distance

We send our tanks and guns

They learned to fight with their hands

(Frank Chickens 1987)

Similarly, in the song "Japanese Girl" they successfully use these same issues of inter-Asian relations to deconstruct Japanese Girl Culture. They assert that the insular security of Girl Culture, through which adult women cultivate an identity of childlike purity, relies upon a corollary cultural phenomenon of immigrant women servicing the majority of Japan's highly visible sex trade:

- I met her on the streets of Tokyo

Waiting at the bus stop looking so vague

She was blown softly by the spring wind

Her face like a woman in the airline posters

(Chorus)

I'm a Japanese Girl

I'm guilty, I'm innocent

Japanese Girl

She had the beauty of mystery and violence

Sugared with patience, smelling like sun

Sometimes I dream of being like that

My basket was full of plastic innocence

"Hellow Kitty" hair clips, pale peach and mint

She didn't speak much Japanese

But her words made me shiver

Her skin was darker than mine

Her eyes were deeper than mine

She was a dream of men's desire

She gave me a smile

She said, "I don't like Japanese men,

It's my job to drink with them"

I was ashamed, I walked away sad

Our virginity, our innocence

Protected by these dark-skinned angels

From our next door country

They are the throw-away angels

Who live in hell

Because I'm a Japanese girl I'm labelled innocent

But now, I feel guilty

My room is a shrine of innocence

Plastic toys, pin-ups, cosmetics

I watch lolly-pop singers on TV

Every day I follow the soap-operas

Because I'm a Japanese girl

I'm labelled innocent

But at night before I go to sleep

I see the neon sign over my shrine

It says in blue and pink letters,

"You are guilty"5

(Frank Chickens 1987)

| 5 During my college years as a Fine Arts major I did a number of projects criticizing gender representations in advertising. I specifically despised advertisements using color associations of baby-blue and pink on models' clothes and other objects to subliminally invoke conservative Male and Female power relations (for example, a photo of a woman taking an aggressive stance toward a man might typically have her wearing blue and the man wearing pink). In this regard, I enjoy the use of blue and pink for the neon sign reading, "You are guilty." |

Their critical eye on sexual relations also turns toward the Lesbian community, such as in the song "Two Little Ladies," which contrasts the notion of a Lesbian relationship as a "safe space" with eccentrically disabling acts of self-seclusion. Along similar lines is "Feed Me," from the 1988 release Club Monkey, which is a love song written from the perspective of a sexual Top whose careless and dog-like treatment of her sex slave is contrasted by the sense of security she derives from emotionally possessing the slave - security that is slowly but surely being destroyed through neglect. The Top croons that a loyal hound never leaves her Mistress, but concedes when she dies all dynamics will reverse as her hound will eat her corpse out of hunger. A disclosure of the Top's secret desire for passivity hides behind her sexual demand for her lover to "Feed me with your security, Eat me aliveノ O carne mio amore, Mangiami per favoriノ" (Frank Chickens 1988)

In addition to the Frank Chickens, Hohki has gained recognition for her solo stage performances combining music, digital video and theater, such as the collection of love vignettes, My Husband Is A Space Man. In this performance the theme of Lesbian and Gay homogenisation (ie., "clones" who conform to stereotypical lifestyle images of Butch and Femme, etc.) arises in "Looking For Me," the video component of which features amoebic micro-organisms of various shapes experiencing romantic dissatisfaction until finally matching up with similarly shaped Globules. As a whole, My Husband Is A Spaceman uses outer space as a metaphor for intra-cultural alienation between genders, as well as inter-cultural themes of movement between cultures and geographical spaces, such as that facilitated by spousal visa sponsorship.

This association between Japanese people, relocation, travel and international tourism was summarized by Hosono in the term "Sightseeing Music." For Hosono, the Japanese preoccupation with sightseeing serves as a metaphor for electronic musicians producing works in several genres, much like a tourist visiting different cultures. Hosono himself produces a wide range of works including Electroacoustic and Ambient experiments, Acid and electronic dance music, Digital Jazz, electronic reconstructions of traditional Japanese music, Exotica and Western Folk Rock. Whereas World Music involves a gathering and bringing together of audio from various contexts into the Western audio marketplace, Sightseeing Music involves an outward excursion to multiple and distinct contexts of production, and an occasional exodus from the (financial and stylistic) limitations of the Japanese audio marketplace. As for the act of performance itself, "touring" takes on a direct relation to notions of recreational tourism.

| 6 Consider critical debates around the cross-cultural productions of producers such as Malcolm McLaren and Paul Simon... or even Vanilla Ice, Madonna and Eminem. |

Despite the directional distinction between World Music (immigrational) and Sightseeing Music (emigrational), both invoke the assumption of music's "universality" and ability to transcend borders. It is a dangerous assertion that, in addition to ignoring the frequent economic exploitation of Third World musicians, overwrites the contexts of production with the foreign release marketplace's cultural preconceptions of that context.6 The desire to perceive cultural diversity through notions of "peaceful understanding" disavows the "disruptive irreconcilability" that Difference also entails. One recent but currently defunct project caught in this representational dilemma was the Foggy Echoes Project, an audio research group/band headed by Shinsuke Sekito. The Foggy Echoes Project was committed to digitally preserving the oral traditions of the Asian continent, including legends, chants and religious stories, through processes of field recording, collage and digital synthesis. Central to the work of Foggy Echoes was a contradiction between their undertaking archival actions as a socially conscious response to the political erasure of cultural difference in Asia, and the rather a-political mystification and reclamation of an intercultural 'Asian Spirit' their music sought to represent. While their motive was the preservation of cultural differences in Asia, their compositional aesthetic of digitally combining culturally unrelated and disparate source materials often resulted in Orientalist homogenization and an erasure of context.

Yet, within their works clear culturally specific themes did occasionally remain. In particular, several of Foggy Echoes' works included traditional Japanese themes of same-sex love and sexuality that do not conform to Western notions of Homosexuality, a sexual model originating in the nineteenth century. In particular, they focussed on classics of Japanese literature representing non-gender-restrictive sexual interaction, such as The Tale of Genji. Sekito, who was aware of the tendency to naively fantasize non-Western-sexual-model sexuality as a hedonistic free-for-all, was careful in his miscellaneous writings to discuss distinct models of Japanese same-sex love that emerged from various cultural sectors including Buddhist monks, the samurai class (often idealized by the merchant class), or commercial transactions with Kabuki actors. He also noted distinctions between onna girai authors (sexually male-exclusive "women haters" typically writing for merchant class sponsors, such as the writer Ihara Saikaku), and shojin zuki (people who had sex between gender barriers). However, as a result of the influx of Western legal and medical discourses during the Meiji era (1868-1912), such distinctions disappeared from modern Japanese literature - a loss of linguistic history that served as the link between such themes and the Foggy Echoes Project's larger concern with preserving Asian oral traditions. It is with a sad bit of irony that preservation of the Foggy Echoes Project itself has been indefinitely jeopardized, as the largely internet-based project is currently without hosting.

Hosono also works a great deal with this notion of preserving and recontextualizing cultural histories. While I am drawn to the ways in which his productions acknowledge cultural identity as a constructed system of material social processes, they also contain an active desire to reclaim essentialist notions of 'natural truth' in personal and cultural identity (again related to the Hippy impulse I mentioned earlier). However, he also has a tremendous sense of humor and is not afraid of bastardizing social influences (humor itself being linked to traditions of laughter meditation). The result is a continual invocation and denial of traditional Japanese cultural signifiers. Undoubtedly the most recognizable manifestation of all these concerns was Hosono's formation of YMO in 1978, with Ryuichi Sakamoto and Yukihiro Takahashi. While YMO was largely perceived in the West as a kitsch 'ethnic variant' of the German Technopop supergroup Kraftwerk, within Japan their technically cutting-edge electronic renditions of traditional Japanese and Western Orientalist melodies represented a critical break from Japanese Pop contemporaries who were fixated on simply emulating the West. YMO managed to re-introduce a notion of distinctively Japanese musical identity to the indigenous Pop marketplace, while simultaneously using parody to undermine such an identity. This play with signifiers emphasized the importance of plasticity and image-management within contemporary Japanese culture.

| 7 The notion of Lunacy remains a key aspect of gender transitioning, as most countries require people to obtain a clinical diagnosis of Gender Identity Disorder (GID) prior to undergoing surgical alteration. For most, this necessity to frame one's desire to transition in relation to a medical disorder poses a tremendous challenge to retaining a sense of personal choice or self-empowerment throughout the transitioning process. |

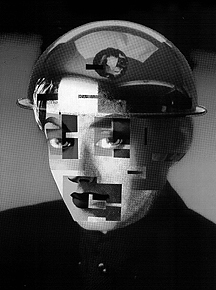

The notion of plastic identity - of being easily impressionable, readily melted down and reformulated - also plays a part in Hosono's incorporation of themes of Transgenderism. Japanese theater, much as in Europe, has a long tradition of cross-gender impersonation. And, like in the West, much of it took the form of female impersonation related to restrictions against women performers. Whereas this tendency has largely disappeared from popular theater in the West (replaced by Hollywood's "ne'er-the-twain-shall-meet" gender splits between the super-hunks and super-models), gender-bending remains a highly visible aspect of Japanese stage and television. This situation enhances the visibility of Transgenderism, but taints the reception of Transgendered people as little more than prankster comedians, or non-threatening and sexless Male-to-Female Stage Queens (both of these preconceptions also exist in the West, but without such avid visibility and reinforcement on a Pop Culture level). Hosono's Transgendered imagery, on the other hand, has consistently been a bit less aesthetically pleasing to the mainstream. It remains unresolved, such as the numerous pastiche portraits of Hosono filling the cover and sleeve of his 1984 album SFX (Figs. 1 and 2). The song "Androgena," from the same album, offered an odd love song contrasting Japanese lyrics about a glamorous and flamboyant lost love (possibly a Stage Queen, although I seem alone on this interpretation) with the Engrish refrain, "LUNATIC ANDROGENA, LUNATIC ANDRO-GENIUS."7 It was also around this time that he produced the chanteuse Miharu Koshi's Female-to-Male invoking album Boy Soprano. (Not to forget Hosono's 1997 release of my album, Couture Cosmetique: Transgendered Electroacoustique Symptomatic of the Need for a Cultural Makeover [Orノ What's behind all that foundation?] on his label Daisyworld Discs.) There is an important distinction between such Transgendered imagery and more commercially acceptable New Romantic imagery of the '80s (which YMO simultaneously dabbled in). Hosono's productions, in all of their varied approaches and connections to Transgenderism, display a plastic interaction with Pop Culture's Transgendered imagery that I find comforting from a non-essentialist perspective.

Figure 1 |

Figure 2 |

The sound of the Japanese marketplace - sound associated with everyday commercial and social space - extends beyond the typical Western boundaries of in-store Muzak, television and radio. Japanese shops broadcast anthems well beyond their storefronts to passersby in the street. Consumers are greeted with loud cries of welcome, verbally acknowledged by every employee passed during the course of shopping, and sent off with a rain of farewells that continue in excessive appreciation after the closing of exit doors. Garbage trucks and other slow moving service vehicles broadcast eternal loops of piercing digital melodies and announcements - electronic surrogates for traditional calls made by passing merchants (the original versions still heard in the evening whistles of tofu vendors selling their products from bicycle baskets). Subway stations play signature melodies on the train platforms to help identify train lines, and in some cases individual stops. ...Not to mention the standard barrage of cellular phones and other miscellaneous items one might personally carry. The digital jingle - that non-musical melody lying in the heart of every battery-powered musical greeting card - also lays at the heart of much Japanese electronic music. "Experimental" producers such as Nobukazu Takemura randomly interrupt electroacoustic works with fluffy verses and choruses played on cheap keyboards. Such compositional strategies seem baffling in the West, best explained as an attempt to shatter the boundaries of High- and Low Art with a bit of Kitsch. But in Japan, such random melodic interjections are so typical of the daily soundscape that they rarely conjure critical notions of Kitsch. The melody is disarmed of its narrative flow and reduced to a sound object - it becomes an instrument.

The use of jingles and melodic overload exudes a somewhat different nuance in the melodically noisy works of Japanese women electronic producers such as Jun Togawa, Takako Minekawa or Michiko Kusaki. (Perhaps the closest thing to these producers in the West would be Blechtum From Blechdom.) In a culture where girls are encouraged to learn the piano as a sign of feminine refinement, but where space and financial limitations prohibit the use of real pianos, there has emerged a generation of women raised on synthesizers and electronic keyboards. The result is a proportionally larger number of women who commercially produce electronic music than in the West - still far from equaling the number of men commercially producing electronic music, but substantially more than I have ever noticed in America or Europe. Unlike Takemura's work, in the works of such women producers the jingle and cute melody are tied to the youthful demands of Girl Culture. By composing in a piercing and almost anti-musical aesthetic of cheap keyboard sounds and home-quality recording, they draw attention to the social and cultural boundaries of women's access to electronic audio technology. This in turn points to the undocumented (ie., commercially unavailable) yet expansive realm of the non-professional woman electronic musician. In my mind, and to paraphrase Hosono, these non-professionals are the GLOBULE 'seeds of stars' who grew up as Japanese hi-tech kids and they are the real NON-STANDARD.

The NON-STANDARD producer may not think her equipment constitutes a home studio. She may only define her performance as "practice." Her concept of audience may only extend from "no one" to "friends and family." She may never record sound to tape, nor record anything into her keyboard's memory. To discuss her actions is to discuss the invisible, the undocumented, the un-provable memory of what we have seen privately but cannot represent through materials to be shown publicly. It seems only appropriate that her tool of choice - that instrument of no respect - should be inextricably associated in everyone's mind with the name Casio. As the story goes, Casio's excursion from watches and calculators into the world of musical instruments was originally no more than the company owner's capitulation to the whims of his son. Never taken seriously within the company or without, Casio's music division did produce a short-lived professional line of instruments during the 1980s, including the FZ sampler series. The FZ was the world's first 16-bit digital sampler, offering excellent filtering and wave synthesis, a large graphic interface, 8 individually assignable line outputs, a mix output, and export to hard-disk capabilities. The FZ far outperformed other soon-following 16-bit digital samplers, both in sound quality and features (I know because I still own and use two FZ-10M rackmounts, both of which were my first two pieces of equipment). However, Casio was unable to overcome its reputation as a musical toy maker, and its professional line was an economic flop. The music division was refocused on non-professional home use, and has successfully remained as such for nearly the past two decades. The NON-STANDARD producer, like Casio's music division, exists and fosters despite the fact that she is not taken seriously. Within this sphere the aim of technology is not technological advancement, nor even MIDI capabilities. It is the non-compatible, non-connectable, non-transferable, identifiably non-professional audio device devoid of expectation (a romanticist might even say "freed" or "liberated" of expectation, although I personally dislike such language). Again, in Hosono's words, "it can be another naturalism (SHIRAKABA-HA in Japan) in this hi-technology society."

As a Transgendered producer interested in openly discussing issues of gender, I am often asked that question on everyone's mind these days, "Why are there more men than women producing electronic music?" This is usually hiding the quite different question of, "How can we increase the number of women producing electronic music?" Personally, I think the answer to the first question is quite simple - take a look at toy commercials broadcast during any children's television show and you will quickly see the radically different relationships girls and boys are encouraged to have with technology - ads involving mechanical or technical imagery almost exclusively target boys (typically hawking robots, artificial weapons, and Boyhood devices of all sorts). As to the second question, we are then left with an issue of linguistics. If a person has been raised to find expression in a particular language - expression via a particular media - what cultural contexts make it necessary for them to adapt and develop a new language or media? One of the keys to developing and spreading practices on a wide-scale basis is wide-scale necessity. But frankly speaking, the fundamental assumption that there is a necessity for more (White?) women producers of electronic music (not to mention Transgendered producers) imbues electronic music with a degree of cultural importance that, at the expense of invalidating my career, I ultimately find lacking. Similarly, given the larger number of women producers in Japan emerging out of a highly gender-biased culture, as opposed to the visibility of women producers in the "egalitarian" West, we can see that the notion of quantity is quite distinct from notions of equality or cultural access.

Despite (because of?) these observations, I am still motivated to challenge exclusionary gender imbalances within both the digital audio marketplace and academia. However, in my view the concern of how to increase the number of women and Transgendered people producing electronic music is like the question of how to increase women-produced pornography. I dare to suggest there are some cultural spheres in which "equal representation" will never exist on a material level, and acknowledging this is not conceding to defeat. Academia and the commercial audio marketplaces' Liberal-minded prioritization of seeking the participation of NON-STANDARD producers does not necessarily entail an increase in the cultural need for such producers... particularly within such a tangential and specialized field as Western Computer Music. I fear any increase in such a need will ultimately rely upon broader cultural changes including, but not limited to, those most general of relationships between genders and technologies (toy machine guns for little Janey, and urinating baby dolls for little Jimmy?). Still, based on the needs of today - the cultural and economic needs of those who produce under unusual and/or unrecognized conditions - we have much reason to look at our NON-STANDARD identities as they exist "in the middle of everything, in a very ambiguous zone," even if it is without hope of equal representation.

In terms of identity - personal, economic and otherwise - many of us find our two feet mysteriously wedging their way into more than two cultural doors at a time, even occasionally tripping upon ourselves. Despite my personal desire for open discourse, combined with my aversion to thematic and political vagueries, I have come to consider Sightseeing Music an appropriate soundtrack for my own stumbling dance with identity issues. For those of us who in some way identify as inhabiting a cultural periphery, letting go of Western egalitarian ambitions need not necessarily result in our acceptance of discrimination, our embitterment, our disappearance or our ceasing of activities. Conversely, it would be both naive and problematic to conclude such a letting go lifts our ideological blinders, or promises an opening into Japanese culture. But I believe it does offer new ways to consider the same old issues: how do we represent our multilateral activities through traditionally unilateral discourses? What activities do we expect to have accepted as "serious" or "real" within existing academic and commercial aesthetic frameworks? And more importantly, which of our electronic music activities perhaps thrive better while existing under the aesthetic radar? As the Engrish rhetoric of Globular Identity Politics so tangentially makes clear, "this is part of the idea."

References

After Dinner. 1983. After Dinner. Osaka: After Dinner. Sound recording.

After Dinner. 1989. Paradise of Replica. CH: RecRec Music. Sound recording.

Foggy Echoes. 2000. Foggy Echoes. Japan: Foggy Echoes Project. Sound recording and internet project (currently unhosted).

Frank Chickens. 1984. We are Frank Chickens. UK: Femme Music. Sound recording.

Frank Chickens. 1987. Get Chickenized. UK: Flying Lecords. Sound recording.

Frank Chickens. 1988. Club Monkey. Germany: Femme Music. Sound recording.

Haco. 2000. Happiness Proof. UK: ReR Megacorp. Sound recording.

Hanayo. 2000. Gift. Germany: Geist. Sound recording.

Hanayo and The Black Dog. 1996. SayonaLaLa. Japan: Media Remoras, Inc. Sound recording.

Hanayo and Panacea. 1999. Hanayo in Panacea. Germany: Mille Plateaux. Sound recording.

Hoahio. 1997. Happy Mail. Japan: Amoebic. Sound recording.

Hoahio. 2000. Ohayo! NY: Tzadik. Sound recording.

Hohki, Kazuko. 2001. My Husband is a Spaceman. UK. Performance and Digital Video.

Hosono, Haruomi (ed.). 1984. "GLOBULE." In Globule. Tokyo: Non-Standard Books: 175-176.

Hosono. 1989. Omni Sight Seeing. Tokyo: East/West Music. Sound recording.

Hosono. 1984. SFX. Tokyo: Non-Standard Music. Sound recording.

Husaki, Michiko. 2001. Don't Do That. US: Hiao Hiao Hiao Records. Sound recording.

Koshi, Miharu. 1985. Boy Soprano. Tokyo: Non-Standard Music. Sound recording.

Minekawa, Takako. 1997. Cloudy Cloud Calculator. Japan: Polystar Co. Ltd. Sound recording.

Murasakishikibu. ~1015. The Tale of Genji. Japan.

Thaemlitz, Terre. 1997. Couture Cosmetique: Transgendered Electroacoustic Symptomatic of the Need for a Cultural Makeover (Orノ What's behind all that foundation?). Tokyo: Daisyworld Discs. Sound recording and text.

Thaemlitz, Terre. 2000. "Why is Fagjazz Meaning." In Fagjazz. Kawasaki: Comatonse Recordings. Sound recording and text.

Togawa, Jun. 1984. Tamahime Sama. Tokyo: Alfa Music, Inc. Sound recording.

Yellow Magic Orchestra. 1979. Yellow Magic Orchestra. Tokyo: Alfa Music, Inc. Sound recording.